Dune Messiah - Novel

- Bryce Chismire

- Sep 29, 2025

- 16 min read

Dune. Frank Herbert's magnum opus, hailed as one of the most exemplary sci-fi novels of the 20th century, transported us into a new world beyond the far reaches of space long before other classic sci-fi epics like Star Wars ever did. And with its compelling characters, epic scope, and even its political intrigue, Dune rightfully cemented its legacy as one of the most legendary novels ever written.

But it was not until 2021 that director Denis Villeneuve had the right creative hand to translate this science fiction masterpiece to the big screen. Splitting the first book into two films, each film was critically acclaimed by critics, including myself, and nominated for plenty of Oscars under their name, including one each for Best Picture. So, the throbbing legacy of Dune still pulsates within its devoted audiences, how matter how it was conveyed.

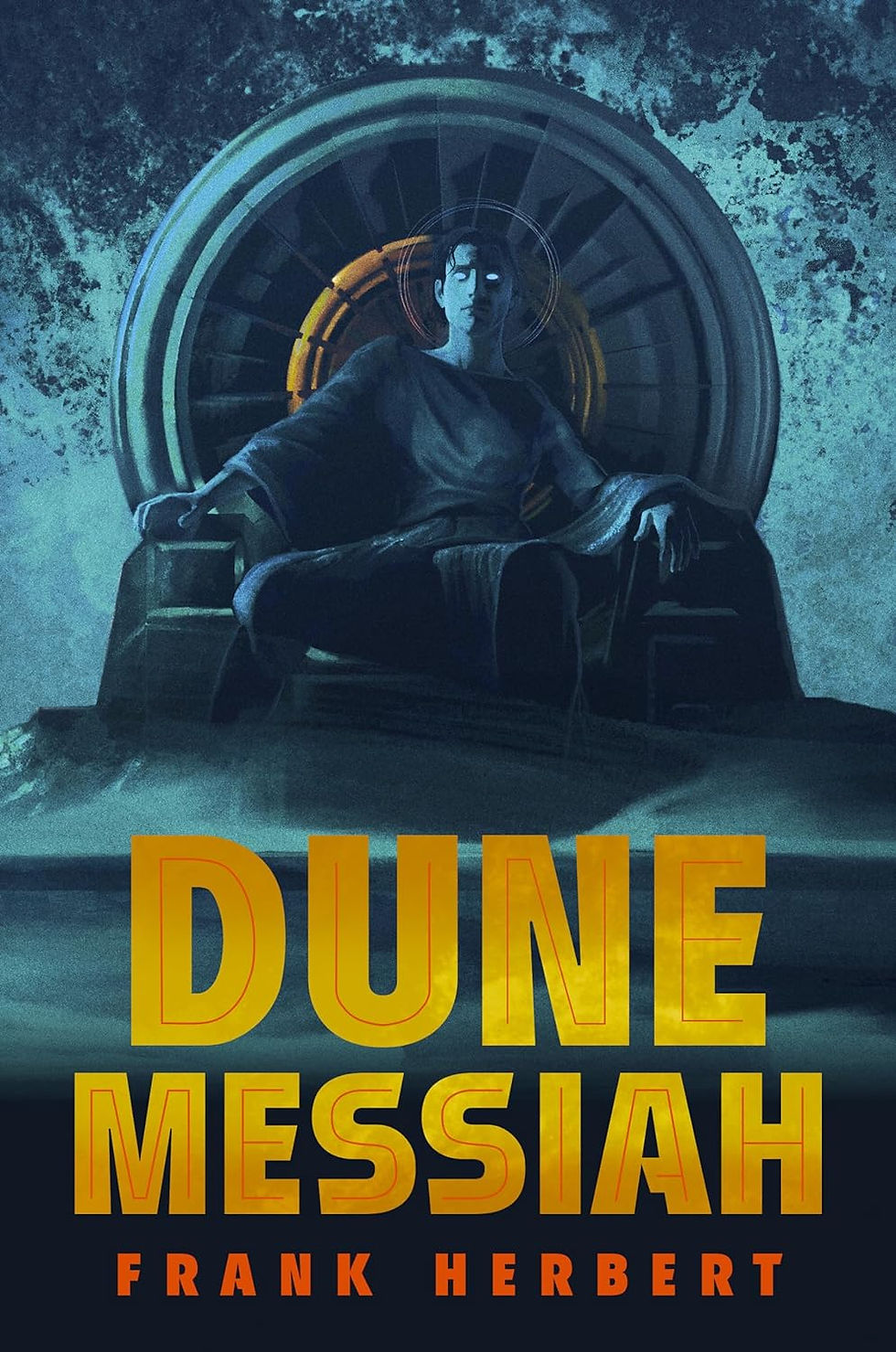

But now, as I wait for the next film to follow, I have finally taken a peek at the next book in the original series – and the one on which movie number three will be based – Dune Messiah. And considering what a masterpiece the first Dune already was, how does this story compare to it?

Well, I was going to say that it felt like Avatar: The Way of Water, where it felt like it was missing some things that made the first story so good, but benefited from others that nearly put this on par with the original. But what Dune Messiah added to the overarching story of Dune was so strong and caught me so much by surprise that I ultimately did not care if some of the best stuff in the first story went missing in this one.

Let’s start with where the story Dune went off to.

Set twelve years after the events of the first Dune, Paul ’Muad’Dib’ Atreides livd up to his promise and made a name for himself as the new Emperor of the Universe, though not quite the kind we expected someone like Paul Atreides to be. Because he had underwent his Imperial promise throughout the universe, he had done more than bring water to the planet of Arrakis. He had also trailblazed his way onto plenty of other planets in the universe, wiped out a few religions, and exterminated a good chunk of the planets in the name of both the Atreides family name and his fellow Fremen tribe. Because of this, the reputation that unfolded in his wake was nothing short of condemnation and utterly unlike what we anticipated someone like Paul to have achieved.

Because of this, plenty of conspirators plotted behind his back to take him down, including Scytale, a member of the Tleilaxu people and a famous face dancer – I’ll explain how that works soon – and a distinctly unique figure named Edric, a fellow Guild member. It also extended to the Reverend Mother Helen Moheim, who resented Paul Atreides for rejecting her propositions for him to become the Bene Gesserit’s prophesied Kwizatz Haderach, and even Paul’s political mate, Princess Irulan. They all plotted to exploit Emperor Paul Atreides’s possible blind spot and exterminate him before he had done any more harm throughout the universe, especially to the Guild associates.

Paul, catching on to the unrest surrounding his affiliates, felt challenged from every side. For one, he and his de facto wife, Chani, plotted to be a mother and father again, not just because they lost their first son during the Sardaukar wars in the first novel, but also so their future heir to the throne would have been born under their blood and not of those like Princess Irulan. Testing his resolve further was the arrival of the Tleilaxus’ supposed ’gift of gratitude’ to him: a ghola of his fallen comrade, Duncan Idaho, who went by the name of Hayt.

Being Paul's loyal sister, Alia became suspicious of Paul’s new affiliate and studied him to know his game and his real intentions with Paul. However, as the two of them spent more time together, they began to develop a slight relationship that would have ultimately determined who Hayt truly was and whether he was Duncan Idaho or just another copy of him.

Would Paul have maintained his hold on the Imperial throne for long? How would he have offset his enemies and repented for his past misdeeds? And could even his most trusted allies have been trusted in these circumstances?

Even before I began reading the original Dune, I knew that Frank Herbert had written six books in the series, each following where the previous one left off. After finishing the first novel, I became more interested in seeing where the story would’ve gone and how it would have managed to do so in such a lengthy span.

As far as additional follow-ups go, Dune Messiah carried a lot of intriguing parallels with the first novel. And it did more than continue what the first Dune unleashed in terms of its philosophical viewpoints and convictions.

As I remembered from the end of the first novel, Paul Atreides promised his fellow Fremen tribe, especially his beloved Chani, that he would bring forth water to the planet of Arrakis, even though Dune Messiah barely delved into the significant ecological impacts of water on Arrakis. Sometimes it touched upon that, like at the end of the novel, when the kangaroo mice and the hawks came to lounge in the plant life grown near Sietch Tabr. However much water Paul transported to Arrakis in the twelve years between the first novel and this novel, it almost didn’t matter. What mattered more was the long-term impact Paul left behind as the new Emperor of the universe. And what did he do?

As you may have noticed from my summary of the story, something downright unthinkable.

And at first, I was uncertain as to what type of legacy he left behind or what he did until he and Stilgar talked in detail about their planetary conquests and what an impact they had on the universe altogether. They mentioned how they had killed 90 billion people, destroyed 90 planets, and wiped out several religions across the universe, probably because they may have thought of them as they thought of the Harkonnens: just several more traitorous groups to annihilate. And it was during this briefing when they even compared their extensive massacres with – and yes, they referred to them by name – Genghis Khan and Adolf Hitler.

I could barely have believed what I was reading. In the first novel, I had always looked at Paul Atreides as a heroic figure who started from nothing only to come out on top with promises to fulfill for his newfound tribe. However, this kind of background, which has been retrospectively described as the Jihad, suddenly painted Paul Atreides as if he had become the most reviled figure in the universe. He set out to be the most extraordinary man in the universe, a prophet, a savior, or a Messiah, as the title said. But judging from the reputation he left behind, he became something even more unexpected, something we had not anticipated Paul of being: a tyrant.

It was strange to think about, because we automatically hated Tarkin’s guts when he went back on his word and destroyed Princess Leia’s home planet of Alderaan in Star Wars. And here, Paul Atreides, a generally likable and interesting ’hero’, did not hide that he and his fellow followers and Fremen had demolished plenty of planets before. So the idea of the most seemingly righteous people in the universe morally going the other way around just made it the most difficult outcome to wrap our heads around. And throughout the novel, as I continued to read it, I always remembered just what a respectable and respected human being Paul Atreides was, while forgetting that, in his promises to his fellow Fremen tribe and his rise into the Imperial regime, he had committed unimaginable offenses across the universe that would have usually painted him as the most hated figure imaginable.

As Frank Herbert would have done best, he conveyed his characters, especially the new ones, with juicy personalities to arouse the readers’ interest, even those that could have benefited from more involvement in the story.

Among the new characters, particularly the enemies, were a crafty Tleilaxu named Scytale, and one of the Guild Administrators named Edric, and because he was always shown swimming around in a tub full of orange gas, it only made his posture and general impression all the more memorable. But what made Scytale memorable was how, since he was a Tleilaxu, he was an accomplished face dancer, which allowed him to easily morph his face into any person he desired, even those who had died.

That’s why the following scene I’m about to address was memorable for its general creepiness. It was when Paul’s sister, Alia, investigated the death of a Fremen-born woman whose skeletal remains were found lying in the Arrakeen deserts. After examining it further, she, along with Hayt, the ghola of Duncan Idaho, suspected that something had been done to the body to make her die so suddenly on this planet, despite the locals of her gender and age usually not having died so early. In this case, they were sure she died from a substance called Semuta.

Later in the story, we got to see Scytale’s crafty side come into play when he posed as the woman who passed away, whose name was Lichna, and who was the daughter of a Fremen and former aide of Paul, Ortheym. For that reason, the more the characters and even the narration spoke of Lichna, including by Paul when he spoke with her about potential negotiations, the clearer it became that Scytale had murdered Lichna and posed as her to give himself an advantage and lurk his way closer to Paul past his defenses.

However, one of the most intriguing parts of the novel centered around Hayt, the ghola of Paul’s fallen comrade, Duncan Idaho. And when I say ghola, I mean a borderline clone.

How did he come to be? It turned out that the Guild Administrators, as well as both the fellow Bene Tleilax and the Bene Gesserit, had a new machine that could have allowed them to take the flesh of any recently deceased person and rework it so they would have brought the original bearer of the flesh to life and potentially as a newborn being capable of following orders. Because they decided to pick Duncan Idaho, one of Paul’s best friends and mentors, as their ghola, that only made it more intriguing as to how Duncan—I mean, Hayt—would have grappled with the idea of being tasked to kill Paul Atreides while also having to wrestle with his Mentat capabilities and his know-how through a new religious philosophy he practiced called Zensunni.

Whereas the first Dune felt like a classical epic set in space, Dune Messiah felt more like a political drama, also set in space. And just so you don’t get the wrong idea, it’s not like the Star Wars prequel trilogy, which dabbled in political negotiations but generally achieved uncertain results regarding how elaborate, well-placed, or even beneficial this was in the long term. With Dune Messiah, the political intrigue here felt more natural, like it was more ingrained in Dune’s DNA than in Star Wars.

While the political intrigue was all fine and very interesting, I believe that Hayt’s quest in the novel provided the heart and soul of the story. Whatever he said, he said them as if he was programmed to say them as he communicated with others, not helped by the metallic eyes he bore. And where it only got even more fascinating was when he began to develop a close relationship with Alia, Paul’s younger sister. She suspected that this thing, this clone of one of Paul’s best friends, could not have been who he originally was, and so was rightly suspicious of him trying to axe off Paul Atreides behind his back. But the longer these two spoke to each other and almost outwitted each other, the more likely a deeper relationship began to blossom between them.

Hopping over to Alia herself, I remembered her being looked down upon by the fellow Fremen tribe as some outcast because of her having been born with the full capacities of a Bene Gesserit Reverend Mother, especially since she was developing from inside Lady Jessica’s womb as Jessica drank the Water of Life. Here, whereas in the last novel, she displayed some of her naïveté as well as her innermost loyalty to Paul, her loyalty was shown all over her, as well as a borderline fierceness in her when it came to her devotion to Paul as he sat on the throne and her dedication to the Atreides name. And again, her developing relationship with Hayt propelled her into the heart of the story.

Chani barely partook in this novel through any means necessary except for when it came to Chani and Paul bearing children again, especially after they lost their first child to the Sardaukar wars in the last novel. Only this time, outside of Chani eagerly awaiting a new child with Paul, she deliberately urged Paul to do this with him as a political ploy. That way, if Paul were to have an heir to the throne, they would have had it where it would not have been borne by Paul’s political fiancée, Princess Irulan. The idea that Chani urged Paul to mate with her and their children, both as mother and father, and as a political tactic, aroused some intriguing motivations for Chani, especially since she was one of the renowned leaders of the Fremen tribe. I was partially bothered by how little involvement she had in this book compared to the first one, but wherever her contributions counted, they sure did count.

As for Princess Irulan, I could not help but look back on her and feel like she was still not taken advantage of as wholly as I wanted her to be, especially compared to the first novel. Either that, or I missed something during the first reading. But what happened was Princess Irulan, having been Paul’s political mate for twelve years as he committed the Jihad, was put in the middle of the crosshairs that went on between Paul Atreides’ rule and the conspirators who wanted to bring him down, like the Tleilaxu and especially the Bene Gesserit, including the Reverend Mother Helen Mohiam, who tried to get back at Paul for refusing to be their Kwisatz Haderach as they envisioned of Paul from the very beginning. But outside of Irulan having been told by Helen how to deal with Paul her own way and see to it that she would have borne Paul’s heir, it ended as soon as Paul ordered that he would have had Chani bear his heir through natural means, while Irulan would have borne theirs artificially. At the end of the novel, Alia admitted to Hayt that Irulan had mourned for Paul after he had suddenly given himself up to one of the Sandworms. For those reasons, a part of me wished that more attention was paid to Princess Irulan and her role in the conspiracy against Paul, especially since she had been by his side for twelve years.

Come to think of it, I wished that more attention was devoted to Scytale and Edric, a Guild Administrator. They both seemed like very intimidating characters, and it would have been cool to see exactly what all they planned to do in the conspiracy if they were to bring Paul down. However, as much as I wanted to see more of them in action, I suppose it would not have been as intriguing if it weren’t for just how mysterious these people were, and how they left me in the dark as to how they were going to achieve their plots against Paul Atreides. And more shockingly, they weren’t alone.

It would have led to another shockingly catastrophic event regarding Paul’s eventual handling of the situation. Paul was wandering through Arrakeen when he found himself in a cul-de-sac and into a most well-blocked off home, where Ortheym lived. What did he do once Paul met up with him there? Ortheym and his wife granted him a gift in the form of a dwarf named Bijaz. At first, he seemed like a generally bumbling and slightly uncertain guy who said he would have done whatever was necessary to be in Paul’s service.

But it didn’t last long, for Paul ran into another issue after he ordered Stilgar, the leader of the Fremen tribe, to carry Bijaz with him. And then, as Paul turned his head around, Ortheym’s house was blown up as it released an atomic compound into the air, and most shockingly, that compound blinded several of the soldiers who were present, including Paul himself. Yep, he too had been subject to blindness from the released compounds. And he had been blind for the rest of the novel. Granted, he still had his friends on his side and his oracular powers given unto him by the Melange spice, but I still did not anticipate seeing Paul be ambushed like this, even if it was meant to bombard the hall of a supposed traitor at work.

Because Ortheym carried that atomic compound to potentially use it against Paul, it showed me just how many alliances and loyalties have been torn apart by Paul’s attempts to bring water to the planet of Arrakis and his devotion to making a name for himself and his fellow Fremen people. In this case, watching him decide to conspire against Paul, as did Scytale, Edric, the Bene Gesserit, and likely Princess Irulan, resulted in overwhelming uncertainties about who was on whose side.

Even with Bijaz, the dwarf, his true colors would have been shown when he spoke more to Hayt, knowing full well that the Tleilaxu created him to deceive Paul, catch him off guard, and slay him and his family. Bijaz admitted to being made the same way for the same purpose. However, it seemed as if he was also a mastermind, as he always devised some deceitful way to trick Hayt into giving in to his ghola side and order him to carry out the orders against Paul, his family, and his people as implicitly as possible.

On top of that, the scene before all this occurred, with Paul meeting Ortheym and his wife as they introduced Bijaz to him? Outside of the hidden atmosphere running rampant throughout the scene, there was something about the scene that left me thinking, “before we had the scenes of the Black Lodge from Twin Peaks, I’m sure we had this.” Why? Because it involved the main protagonist dealing with otherworldly people and a dwarf figure in a mysterious room. I don’t know if that was the general connection people made, but that’s the impression I got when I read the scene.

But one of the other most important scenes in this book occurred even before that. Hopping back to the first novel, do you remember what I said about how mesmerized I was by the scene of the Fremen dispersing the water of Jamis into the pond full of water collected from the remains of all the Fremen who had passed on? While the scene I’m about to discuss wasn’t on par with this scene, it still stuck with me because of its more internal implications.

It occurred when Paul attended an audience and watched his sister, Alia, perform a ritual where she and a chorus behind her enacted a recitation and had the audience members partake in questions that would typically have demanded her expertise and godlike powers of healing.

There’s just something about this scene. It felt like Paul was watching more than just a family member performing. There’s a part of it that felt like Paul was watching, as part of the audience, the legacy that he, his family, and his political affiliates created. Exactly what kind of legacy did he mean to leave behind? Especially if it all started with his alliance and loyalty to the Fremen people and his promise to bring water to Arrakis? Because he and Stilgar mentioned how much of a long-term massacre they had accomplished throughout the galaxy and the universe, what he saw Alia performing was part of what he meant to leave behind him all along. How did he feel about being viewed as gods and messiahs rather than proud emperors? Was he proud of the legacy he left behind after massacring so many people, destroying so many planets, and wiping out so many religions, when his original intent was to be viewed precisely as Alia was viewed on the stage? All those questions were seemingly whirling around inside Paul’s head just as much as it was circulating between the characters throughout the story. And it all seemed to run like clockwork despite some parts of the story not being given as much exposition as I feel it deserved.

I said it as I finished up the novel, and I will say it again: what it lacked in terms of its epic scope, it made up for dearly with its political intrigue and, with it, the surprising blurriness between good and evil.

Speaking of which, besides Paul and Stilgar mentioning how many massacres and planetary conquests they achieved throughout their twelve years of universal rulership, Stilgar had also planted at least a dozen Atreides banners, one on each planet. Because I looked at Paul and still thought of him as the hero that he was in the last novel, the Tleilaxu, Scytale, Edric, along with the rest of the Guild Administration, and the Bene Gesserit, including Helen, the Reverend Mother, I consequently looked at all of them with a shred of distrust and disapproval, as if I knew they were up to no good when it came to Paul Atreides. However, when you look at just what a catastrophic and unworthy reputation Paul left behind in his Imperial rule, it suddenly made me look at all of the conspirators in the story like there’s some justifiability behind all their actions, as morally gray or black as they were.

That’s another reason I’m willing to give Dune Messiah credit where credit is due. Even if the lack of an epic scope keeps this from being a 5 out of 5 book, as I view the first Dune novel, what propels it into a 4.5 out of 5 novel for me, again, was the political intrigue and moral blurriness running rampant throughout the story.

One of the other most intriguing aspects of Dune Messiah was its collective reputation for the direction it took the story of Dune. When it was first published in 1969, many readers were at odds over the downhill turns that Paul Atreides took as a character because of his actions as part of the Jihad. However, according to Brian Herbert, Frank Herbert’s son, Frank planted the seeds that would have eventually germinated into the moral and political chaos erupting throughout Dune Messiah in the first novel, and that, yes, there were some hints of Paul becoming a feared figure rather than the Messiah that he tried to be.

Going further, Brian Herbert talked about Frank Herbert’s background as a politician and how he warned that the most dangerous leaders throughout all of history were generally the most charismatic, and that he considered Adolf Hitler and John F. Kennedy as those types of leaders. He considered their charisma strong enough to sway people into doing their own bidding, and potentially would have viewed Paul Atreides the same way for what he brought with him when he collaborated more with the Fremen people and established himself as Muad’Dib.

And because of what had been generally accomplished throughout this novel, everything about it hit the right marks, and in so doing, proved itself as a more-than-worthy sequel to a sci-fi classic like Dune. The characters were reevaluated in more gray areas than before, the stakes were very intriguing, the continuity of the plot was as organic as it was unexpected, and the ending was surprisingly bittersweet, if also uncertain. Without giving anything away, all I can tell you is that some significant changes did occur with the characters, but not necessarily out of malice, and that the sudden ascension or descent of the characters in the story would have set the stage for what was to come next throughout what Frank Herbert planned to continue of the Dune series. And because, with this sequel, Dune went from being an epic story of good versus evil into a political mystery with twists and turns and alliances being built, destroyed, or rebuilt, it only made me feel more intrigued to see what the next novel, Children of Dune, would have had in store, and also, on a side note, anticipate how Denis Villeneuve would have conveyed this story after hitting it out of the ballpark with Dune: Parts One and Two.

I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little death that brings total obliteration. And you should not be afraid to reevaluate, as this novel would promise to have you do.

My Rating

A strong A-

Comments